Huishu DENG, Heritage, Anthropology and Technologies (HAT), College of Humanities, EPFL

The photos taken by visitors to the site, defined as user-generated photos, have been used as a direct medium to study how the general public perceives and attaches to a particular place, as the action of taking a photo is triggered not only by the immediate environment, but also by many aspects of place attachment: attention, perceptions, preferences, memories, opinions, etc. (Tieskens et al., 2018). The anthropologist John Collier was the first to use photography as a tool to study human perception (Collier&Collier 1986). Since then, handing out cameras to participants or self-directed photography (Dakin 2003; Markwell 2000) have become widely accepted techniques for assessing perceived/preferred public space. In recent years, the proliferation of photo-sharing on social media such as WeChat and Weibo has opened up the possibility of collecting large numbers of user-generated photos. It is also a way to engage a wider range of visitors over a longer period. Moreover, with the application of advanced computer vision technologies, such as automatic image classification and visual content recognition, it is possible to extract and analyze information from thousands of photos (Vu et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2020).

This research developed a manual-computer hybrid method to collect and analyze thousands of photos from the WeChat Channel (a special platform embedded in WeChat) and Weibo (微博). These platforms are publicly available and allow for the collection of user-generated content based on a prior publicity agreement between the users and the platforms. The aim of this research is to investigate which elements of a mega-event-driven urban transformation site are perceived and preferred by visitors, and to what extent they are attached to visitors. Mega-events, such as the Olympic Games, have been globally significant occurrences in the past decades, associated with large-scale transformations of cities and regions through their legacies. However, mega-events are widely considered a significant drain on resources in the long term and are generally not welcomed by local communities. According to Müller (2015), one of the primary contributing factors to this failure is the detachment between the event site and the citizens. The place rarely attracts people’s attention and offers limited triggers to encourage people to stay longer; meanwhile, people find it hard to connect with the place through common symbolic meanings or the continuation of memories from individual on-site experiences. To reconcile the disconnection between mega-event sites and their visitors, the first step would be to study the mechanism of on-site perception.

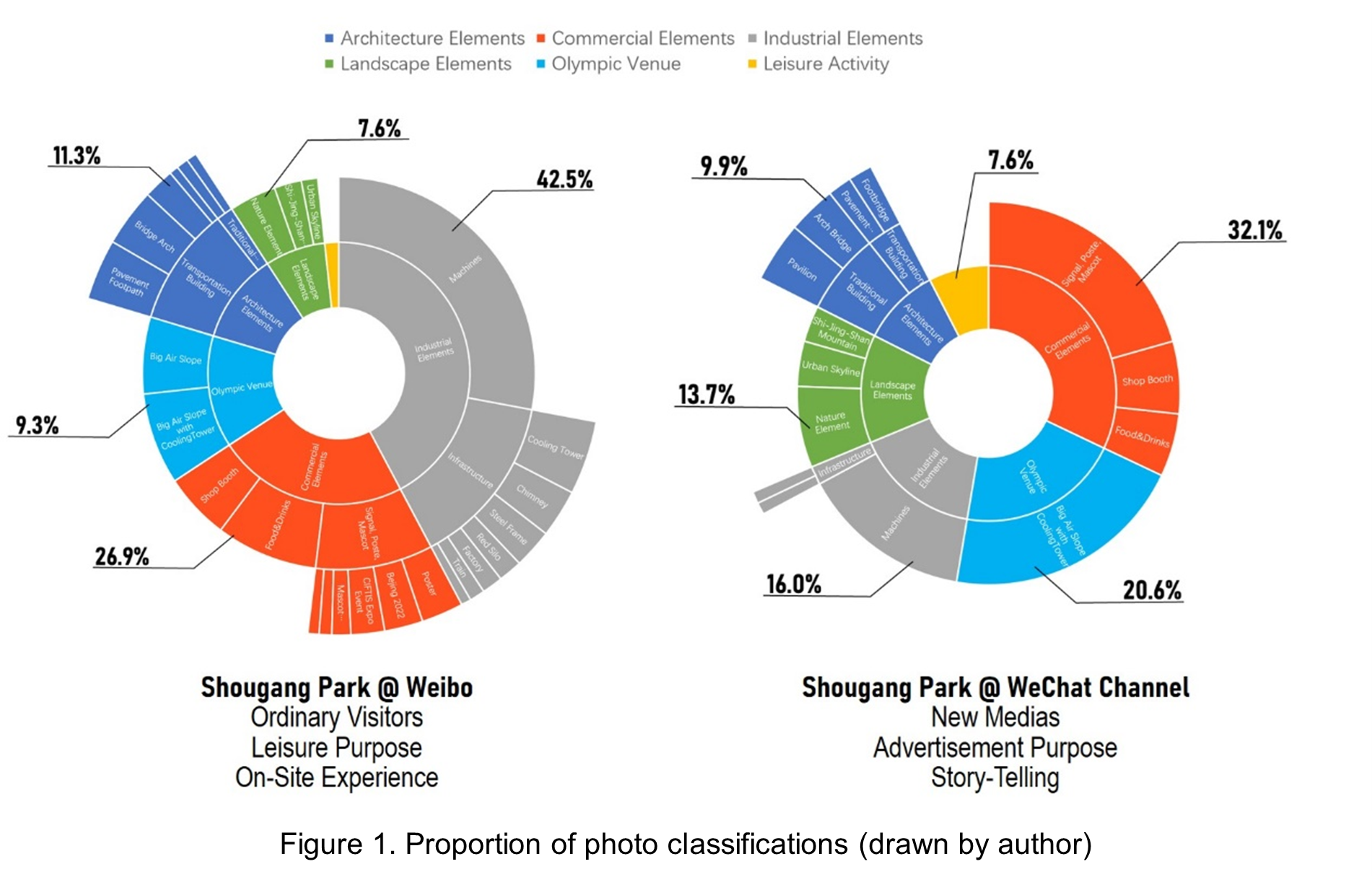

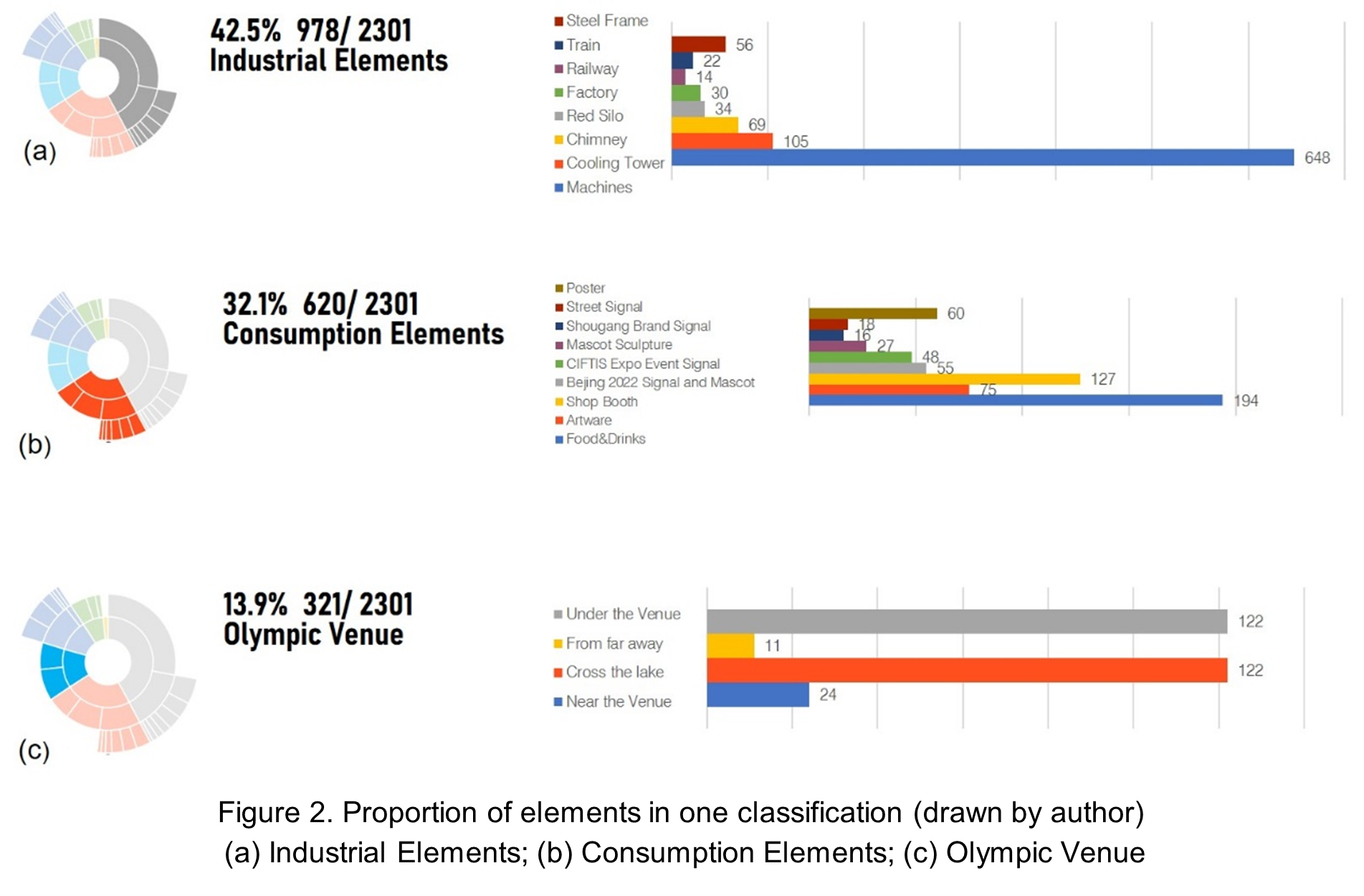

The Shougang Park, an industrial heritage site that has been renovated as the Big Air Venue for the Beijing 2022 Olympic Winter Games and as a public park in the post-games period (after February 2022), is selected as the case study for this research. Firstly, the Weibo API was used to download 4438 photos with the geotag « Shougang Park » taken from June to September 2022. In addition, 220 photos posted on the WeChat Channel were manually collected as there was no public API available. A Python programme was created to classify these photos into different groups based on their visual similarity. The programme employs the Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) algorithm VGG19 to vectorize the images and K-means clustering to cluster the vectorized images, which is a popular unsupervised machine learning method. Finally, the photograph groups are given labels based on their content characteristics. Figure 1 presents the analytical outcomes of user-generated photos from Weibo and WeChat Channel. The photos are classified into 6 groups: architectural elements, commercial elements, industrial elements, landscape elements, Olympic venues, and leisure activities. As evidenced in the figure, industrial elements and Olympic venues account for the highest proportion of photos. To a certain extent, the co-existence of the Olympic venues and the industrial elements in Shougang Park has made both of them more attractive to visitors. The significant proportion of commercial elements also indicates that the commercial operation of Shougang Park plays an active role after the Olympic Games. Moreover, by focusing on a certain category, the more perceived/preferred specific elements can be revealed. For instance, Figure 2(a) highlights that specific steel machinery receives more attention than other industrial elements, while Figure 2(b) displays which promotional products are more popular among visitors. It has also been discovered that visitors generally prefer viewing landmarks from comparable angles. Figure 2(c) demonstrates that the Big Air Slope is photographed from four major perspectives, with two particular perspectives being more favored.

In conclusion, the approach of using computational tools to deal with large amounts of user-generated data from social media represented by WeChat has both potential and risks. On one hand, this approach can uncover new insights that may be difficult to obtain through manual analysis of offline data. For example, in the study of Shougang Park, when hundreds of photos are gathered and analyzed, the tastes of the people who visit industrial heritage sites begin converging. It is a way to gather opinions from the grassroots and turn them into reliable references for decision-makers, planners, or designers. However, this approach poses risks due to the limitation of social media user groups and the lack of characteristic data of users. Although there has been an increase in elderly social media users in China, the dominant user group is still the Generation Z, which may bias the results of the study. Additionally, information about user characteristics like age, occupation, and gender is almost unavailable due to publicity and ethical reasons. This makes in-depth attributional studies difficult. The WeChat-oriented approach offers new bottom-up perspectives on previous research, but more comprehensive methods are necessary for better integration.

(a) Industrial Elements; (b) Consumption Elements; (c) Olympic Venue

Huishu DENG, Heritage, Anthropology and Technologies (HAT), College of Humanities, EPFL

Contact: huishudeng@gmail.com

This contribution was reviewed by Pascale BUGNON and Yali CHEN.

Suggested Citation:

DENG, Huishu (2024). « Discovering Common Perception of Beijing 2022 Big Air Venue through Photos from WeChat Channel & Weibo: A Computer-Assisted Approach ». In Blog Scientifique de l’Institut Confucius, Université de Genève. Permanent link: https://ic.unige.ch/?p=1565, accessed 03/03/2026.

References:

Collier, J., & Collier, M. (1986). Visual anthropology: Photography as a research method. UNM Press.

Dakin, S. (2003). There’s more to landscape than meets the eye: towards inclusive landscape assessment in resource and environmental management. Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 47(2): 185-200.

Markwell, K. W. (2000). Photo‐documentation and analyses as research strategies in human geography. Australian Geographical Studies 38(1): 91-98.

Müller, M. (2015). The mega-event syndrome: Why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it. Journal of the American Planning Association 81(1): 6-17.

Tieskens, K. F., Van Zanten, B. T., Schulp, C. J., & Verburg, P. H. (2018). Aesthetic appreciation of the cultural landscape through social media: An analysis of revealed preference in the Dutch river landscape. Landscape and urban planning 177: 128-137.

Vu, H. Q., Luo, J. M., Ye, B. H., Li, G., & Law, R. (2018). Evaluating museum vis-itor experiences based on user-generated travel photos. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 35(4), 493-506.

Zhang, K., Chen, Y., & Lin, Z. (2020). Mapping destination images and behavioral patterns from user-generated photos: A computer vision approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 25(11): 1199-1214.