[:fr]Ozan Sahin

This article reports on the 11th annual meeting organised by researchers working in the field of Studies of Expertise and Experience (SEESHOP11). The workshop was hosted by the Confucius Institute of University of Geneva and was held on 20-21 May 2017 and continues a series that has included meetings in Cardiff University (UK), University of California (US), Arizona State University (US) and University of Waterloo (CAN). During the workshop, which was held in the Confucius Institute’s dazzling 19th century villa Rive-Belle, we hosted a total of 19 researchers from social science, humanities and law faculties around the world. This article is a brief report of this event and how it is related to Chinese studies and the works of Confucius Institute.

Context: Studies of Expertise and Experience

Decision making in public domain has never been an easy task, especially in the democratic societies where decisions that concern a much broader public may be taken by a few specialists. The difficulty is how to ensure that the choice of the few “specialists” is indeed the best option for the general interest. This is not just a matter of abstract values such as democracy or the general interest, because these decisions often have concrete and practice consequences. For instance, catastrophes caused by human error such as Chernobyl and challenger, or more recently the Fukushima incidents made us think, once again, on the question of specialist expertise, and the legitimacy of such experts’ in the processes that frame and inform decision-making in the public domain. Notably, the emerging field of Studies of Expertise and Experience (SEE) has become a realm in which researchers from various disciplines can investigate the nature of knowledge and expertise, as well as how they are being produced, acquired and transmitted within a society.

The debate about the nature of knowledge has a long history but one particularly important moment for SEE is Michael Polanyi’s introduction of the idea of “tacit knowledge”[1]. The idea of tacit knowledge can be best illustrated with an example. Imagine you are walking in your neighbourhood and someone asks you the direction to go to the closest bank. Having the correct information about bank’s localisation you are perfectly able to describe how to go to the bank: continue straight, after the traffic lights turn left, and then turn right, etc. Now, imagine that the same person wants to go to the bank by bicycle but that she doesn’t know how to ride a bike. Assuming you are the best cyclist in your city, the person now asks you to tell her how to go to the bank by riding a bike. You can still use a very clear language and give the instructions of which direction to go, but when it comes to explain how to ride a bike the language does not seem to reflect your true degree of knowledge on bicycling. Polanyi calls this type of knowledge “tacit knowledge”, a type of knowledge that cannot be manifested in explicit terms, at least by the sole use of the language.

In their previous works, Professors Harry Collins and Robert Evans from Cardiff University, have argued that science studies can be described as going through three waves[2]: a first wave where the only plausible and legitimate knowledge is that which is a product of objective scientific research, a second wave in which science studies scholars adopt a more constructivist perspective and recognise the necessity of social and cultural factors in the production on scientific knowledge; and a third wave of science studies in which the focus shifts from the deconstruction of truth to the reconstruction of expertise[3]. In particular, Collins and Evans argue that STS should explicitly address normative questions such as the role of scientists and others in the making of technological decisions in the public domain. It was this paper, and the research agenda it set out, that gave birth to the SEE[4] and a series of international workshops (SEESHOPs) devoted to developing its theories and methods[5].

Theories of Expertise in Action

One of the domains in which SEE researchers are exploring issues relating to expertise is the field of law. SEESHOP11’s law session, which was led by Professor Nicky Priaulx, from Cardiff University, included Ann Potter’s work on “Judging social work expertise in care proceedings” in Great Britain[6]. Potter, from Manchester Metropolitan University, presented the insights of her research and showed that since the adoption of the new Children and Families Act in 2014 there have been changes in the ways independent experts are used when taking decisions about whether a child should be removed from their family. Apparently, judges now rely on the much more extensively on information provided by the social workers as evidence. Potter’s research can help us explore and understand the consequences of this decrease in the number of independent experts in the care proceedings.

In the same session, Jaako Taipale, from the University of Helsinki, presented his work on dilemmas judges face when choosing the ‘right’ expertise in a trial where the parties might bring up to six different experts on medical science and technology[7]. The latter being a relatively new and controversial matter, there are numbers of issues where experts’ opinions present many disagreements. In his research, Taipale is interested in analysing “judges’ discrimination of factual evidence” when choosing which expert(s)’ opinion to accredit. Finally, Professor David Caudill from Villanova University presented his work on the practice of hiring “dirty experts” before a process of litigations in US courts[8]. The purpose of this practice, apparently very common in the US, is to make a kind of simulation so that they can note down what kind of arguments can be developed against the real or “clean” experts that will be used in the trial itself. Whilst this practice may serve the laudable purpose of reducing the likelihood of bad science being presented in court, it may also have the (unintended) effect of preventing the court from considering the impact or other, more legitimate, controversies.

In our days where the technological progress means that machines are slowly replacing humans to execute certain tasks then machines may be considered as ‘experts’ in those tasks, bringing us the questions about how ethics and accountability of these practices. In this context, Jathan Sadowski[9], from Arizona State University, examined how algorithms written for computer programs are used to assist and inform decisions about the sentencing of offenders and in predictive decisions made by police forces about where and how to allocate resources. Collin Robertson[10], on the other hand, showed how the development of new technologies for connected devices such as mobile phones and tablets can open the doors of science wider than ever to the broad public. He argued that environmental issues have the potential to increase the opportunities for citizen-scientists to collect and analyse scientific data. In this respect, Robertson’s work highlights one of the ways in which theories and methodologies developed by SEE can be used to promote developed and accountable modes of participation for ordinary citizens in different stages of scientific research.

Michael Gorman[11] also focussed on expertise, but in the context of commercial organisations rather the public domain. He was particularly concerned with contexts in which relevant actors – either internal and external to the organisation – are unable to avoid deviant practices such as in the cases of Challenger and Columbia disasters[12], or Gorman’s example of the collapse of Enron oil company. With this example, Gorman demonstrated how deviance can be normalized within the organisation and he argued that “interactional experts”[13] can bring solutions as their expertise enables them to understand problems from different, and sometimes competing, perspectives. In a similar way, Darrin Durant[14] is questioned the trade-off between the democracy and the ceding of authority to so called “experts” via two case studies, the South Australian blackout of September 2016, and the current Canadian nuclear waste disposal repository process.

Imitation Game Research

In addition to new theories of expertise, SEE has also developed a new method – the Imitation Game – designed to explore the nature of one particular type of expertise — interactional expertise – and a number of papers at SEESHOP 11 reported on applications of the method.[15] Philippe Ross[16], associate Professor from University of Ottawa reported on a study in which he had used the method in media studies research to explore how well media professionals who are implicated in the production of media commodities know their audience. Eric Kennedy[17], used the example of US fire department, where executives from different specialisms must collaborate in order to deal with an emergency situation, to propose a combination of survey methods and interview based Imitation Games that could collect scientific data but also provide solutions to the problems of communication between different domains of expertise.

In her presentation, Shannon Conley[18] made a distinction between expertise and competence, arguing that we should not necessarily search for experts in a specific domain, but maybe consider the importance of competence by putting the emphasis on “interactional competence”, which is the ability of executing a task acquired through socio-professional relations rather than an institutional certification. In a similar vein, John McLevey[19] argued that researchers often confound the three distinct categories of information, knowledge and expertise and that social networks researchers in particular often ‘ignore the empirical questions about knowledge’; the typology of expertise provided by SEE provides one way of avoiding this problem.

Researching Chinese Migrations

As we see, SEE has insights that may interest many disciplines and domain of research, and Chinese studies is no exception. For instance, Confucius Institute is administering a research project on migrations, integration and diversity in modern China that links Chinese studies and SEE. Before explaining the project in more detail it is necessary to explain some important facts about contemporary China and, in particular, the unique demographic phenomenon of its “250 million floating population”[20].

For the occasion of the 11th meeting of the SEESHOP, the Confucius Institute invited Professor Duan Chengrong, a specialist on Chinese migrations, to give a public lecture on the subject. Professor Duan’s works are very helpful for understanding this colossal human flux in a society where the movement of populations is highly regulated.

The characteristics of China’s internal migrations are determined by its unique family registration system called hukou (户口) under which most migrants keep their official residence in their hometown. The creates two distinct kinds of migration:

- Migration with hukou, which accounts for about 25-27 million people annually, and which grants migrants an official status that gives them rights to state services such as employment, schooling, health care and so on as other local residents,

- Migration without hukou (the 250 million floating population) where migrants have such official status and, as a consequence, no formal right to access to these public services.

Before 1978, it used to be almost impossible for Chinese citizens to migrate without hukou. Since the early 1980s, however, this has started to change, with the rise of China’s economic development and the emergence of private sector has creating a growing need for labor in the cities. As a result, many people living in the rural areas, where they may have difficulties gaining employment in agricultural production, have chosen to move to the cities where new opportunities being created every day. Although living and working in the city, these people do not have urban hukou and for this reason are called “the floating population” (流动人口)[21].

In his lecture, Professor Duan described his research and the trends in the evolution of China’s migrations that it had revealed. First of all, we note a very sharp increase in size of the floating population. In the 1980s there are only about 6 million people in the whole country living as migrant; by 2015 this number had become 250 million, an increase of about 40 times in a few decades. This increase is not without consequences. Dealing with the problems and needs of this huge population is very difficult for the government, especially when we consider that a significant proportion of these migrants are unofficial, which means their presence — but also their problems and needs – may be invisible for the authorities.

Second, we also observe a strong concentration of migrants in the coastal cities as these constitute the most developed regions of the country. These cities offer new job opportunities and better living conditions for the new arrivals that the rural areas they are leaving. The combined effect of the rapid increase in the number of the floating population and the choice of developed coastal regions results in a high concentration of the floating population in cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, which have floating populations of 8.22 million and 9.81 million migrants respectively[22]. With these numbers, we note that in Beijing the floating population makes up 35.9% of the total population and in Shanghai the proportion is 39%. In Shenzhen, the floating population is an even higher proportion – 77% — with a total floating population of 7.7 million migrants![23]

Finally, the age pattern of the floating population and the motivations for migrating are also changing. Before, most migrants were working age people, but today there is a tendency for migrants to bring their families with them, sometimes even their parents, who not only accompany them throughout the migration process but become, themselves, migrants. Likewise, there are more and more women moving, either independently or with their families. The new comers are often better educated and work in skilled jobs.

Professor Duan concludes that these changes are reshaping the migrants’ profile in today’s China, and the country remains unprepared for the needs of such a large floating population that has distinct characteristics. In particular, without expertise on the evolution, experiences and aspirations of the floating population, they risk developing policies that are ineffective and fail to manage this unique demographic phenomenon. In the remainder of this article, an ongoing research project within the Confucius Institute of Geneva University, and a relatively new and innovative method for studying the socio-cultural integration of China’s floating population, that aims to address this problem directly will be will be described.

Researching Migrants in Beijing

The position taken in this study is to consider that the members of any given social group are experts in their own culture. For example, a person who was born and lived all her life in Beijing would know what it is like to be a Beijinger (i.e. an expert in Beijing culture). In the same way, we can accept migrants as the experts of their own, rural, culture but the crucial question for their integration is whether they can also become experts in the culture of their new, urban, home. Using theories developed by SEE, we can argue that a non-member of a society – i.e. a newly arrived migrant – can, after spending enough time within that society and having prolonged social relations with its genuine members, can develop enough knowledge about the culture and practices of that group to enable her to hold meaningful discourse with them. In the language of SEE, we would say that the migrant has developed interactional expertise in the practice of being a Beijinger. The concept of interactional expertise developed by Collins and Evans[24], is important because it suggest that different groups can come to understand each others’ experiences even if they do not share fully in each others’ practices. In other words, migrants and Beijingers can come to understand each others’ experiences through shared talk even if they lead lives that otherwise very different. The question to ask at this point is “how do we know if somebody has interactional expertise?” The answer lies within the Imitation Game.

Initially known as the “Turing test”[25], the Imitation Game is a quasi-experimental method that generates both qualitative and quantitative data. In its most simple format, it is a game played by individuals who are drawn from two different social groups whose experiences are assumed to be different in some way (i.e. men vs women, migrants vs locals, etc.). Participants to the Imitation Game are required to play three roles; the role of judge in which they formulate questions and ask them to the other participants, the role of pretender, played by a member of the other group who is tasked with trying to convince the judge that they are the members of the judge’s own social group (i.e. if the judge is a Beijinger, the pretender would be a migrant who should try to convince the judge that she is also a Beijinger), and Non-Pretender (a genuine Beijinger in this example) who must answer honestly. The aim of the game is for the Judge to set questions and, by comparing the answers, work out who is a member of which social group. If the judge is not able to identify the pretender correctly, then we say that the pretender has interactional expertise in culture of that social group as she is able to take part in the discourse of that culture without being disclosed as an outsider.

The method, after being introduced by Collins and Evans in 2006[26], has been funded by the European Research Funds in 2011 for a five-year research project, and since then it has been used in a large variety of studies. One of the fields that the method has been applied is the migration studies. Notably, Confucius Institute’s PhD candidate Ozan Sahin is combining the Imitation Game method and the SEE theories with that of Chinese studies for his research on the socio-cultural integration of Hebei migrants’ in Beijing municipality[27]. The objective of this study is to explore how different social groups, in this case “migrants” versus “locals”, interact with each other within urban areas. The findings are expected to help understand:

- How the members of different social groups identify themselves with regards to other social groups

- Their vision and understanding of other groups’ members

- How cultural differences influence migrants’ integration?

In Beijing, migrants from the same city or province often prefer to live and work in the same compounds as their fellow villagers, where they often work excessive hours for a very low income. Many don’t see anywhere other than their working and living space and have little or no interaction with local people. We argue that this is likely to leave migrants’ isolated from the host society and make it difficult for them to fully integrate into the urban life. Thus, the purpose of this research is to apply the Imitation Game method to measure the correlation between the intensity of interactions with the local population and the level of migrants’ integration.

Before adapting the method for his research, Ozan Sahin and Xu Jia from Renmin University organised two trial sessions of Imitation Game at the Renmin University of China in the summer of 2016. Below we present the first findings of this research.

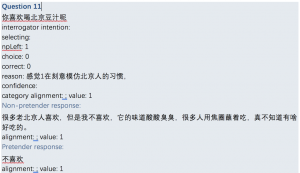

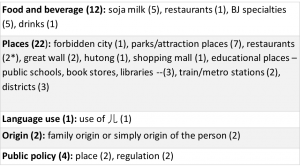

For the first trial session of the Imitation Game, a total of 10 Chinese participants were took part (5 Beijingers and 5 migrants) and 48 target expertise questions were asked. We recorded the dialogs between the players and created question-answer sets for each player (see figure 1 below). When analyzing the results, we noticed that questions asked by Beijing judges can be grouped into 5 general categories: food and beverage, places in Beijing, language use, origins and Olympic games. These categories and their sub-categories are shown in the table 1 beneath.

Figure 1 Imitation Game dialog example

From these findings, we notice that most of the Beijing judges (i.e. participants of the experiment who are originally from Beijing) ask questions which are related to migrants’ experiences and knowledge about peculiar places and local culture of food and beverage which, we assume, they think migrants will not have experienced. If we do accept the Beijing judges as experts of their own culture, we can observe that for them the criteria that distinguishes a Beijinger from a migrant consist of – or at least includes – having enough information about these subjects and being able to talk about them as if it is a part of one’s own culture. Interestingly, the expectations of the Judges were sometimes confounded as our research found that the success rate for migrants pretending to be Beijingers is about 60% (3 out of 5 players convinced the judges that they are locals), suggesting this knowledge is more widely distributed than Judge’s thought and that migrants are better integrated (at least in the sense of having interactional expertise) than Judge’s expected.

Table 1 Question types

That said, it must be noted that our sample was very small and was mainly composed of university students. As such, these results cannot be used to make any general conclusions. Nevertheless, they have been useful in drawing out some general features of the floating population and, most importantly, developing a new version of the Imitation Game software for Chinese users that will enable us to widen our population sample by having more participants with more diverse profiles. For this purpose, the author of this article is developing, with the collaboration of Jacky Bossey from SAE institute Geneva, a new version of the Imitation Game software specifically designed for Chinese users: 伊迷他心 (Yī mí tā xīn, literally “(S)he cheats his heart”).

One of the objectives of this research is to go beyond simply identifying the problems experienced by migrants and to offer possible solutions. For example, by playing Imitation Games over a period of time, it will be possible to observe the effects of an increase in the interactions between the migrants and the local population. Such an increase can be encouraged and facilitated within the Imitation Game by, for example, distributing vouchers to participants that enable them to visit a cultural monument, restaurant or other cultural space with one or more players from the other group. In this way, the Imitation Game can be used to offer migrants access to the local culture and, in so doing, increase their stock of interactional expertise. As players who have received such vouchers return to play new sessions of the Imitation Game we will be able to compare the results obtained before and after the intervention and see whether an improvement in terms of migrants’ integration (i.e. an increase in their level of interactional expertise) has occurred.

Cette contribution a été relue par Robert Evans

SAHIN, Ozan. « From technocracy to citizen science: The nature of expertise and the place of experts in our societies ». In Blog Scientifique de l’Institut Confucius, Université de Genève. Lien permanent: https://ic.unige.ch/?p=1131, consulté le 04/19/2024.

[1] Polanyi, M. (1967). « The tacit dimension ».

[2] Collins, H. M., & Evans, R. (2002). « The third wave of science studies studies of expertise and experience ». Social studies of science, 32(2), 235-296.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See also SAHIN, Ozan. (2014). « L’Intégration en tant qu’expertise interactionnelle : L’Imitation Game comme outil de mesure du niveau d’intégration des étrangers en Suisse ». Non-published M.A thesis, University of Geneva. (A printed version is available at the Geneva University library in UniMail. An electronic version can be requested from the author of this article).

[5] SEE can be thought of has having two elements. A ‘technical’ element that focuses on the nature of expertise and which is best summarised in Collins and Evans’s (2007) book Rethinking Expertise, and a political element that focuses on the relationship between expertise and democracy that is set out in their more recent Why Democracies Need Science (2017).

[6] Ann Potter (Manchester Metropolitan University), “Judging social work expertise in care proceedings”

[7] Jaako Taipale (University of Helsinki), “The usefulness of meta-expertise in examining judges’ discrimination of evidence”

[8] David S. Caudill (Villanova University), “Dirty experts: their use, and what they tell us about law’s appropriations of expertise”

[9] Jathan Sadowski (Arizona State University), “Predictions and Premonitions: Algorithms as Experts in Sentencing and Policing”

[10] Colin Robertson (Wilfrid Laurier University), “Environmental citizen science as a novel application for studies of expertise and experience”

[11] Michael E Gorman (University of Virginia), “Trading zones, interactional expertise and moral imagination”

[12] See also Vaughan, Diane. « The dark side of organizations: Mistake, misconduct, and disaster. » Annual review of sociology 25.1 (1999): 271-305.

[13] People who have acquired a certain level of expertise only by the means of intense interactions with the certified experts. (Also see “interactional expertise” below.)

[14] Darrin Durant (Melbourne University), “Saving expertise”

[15] For details of the Imitation Game see: Collins, Harry M. and Robert Evans. 2014. “Quantifying the Tacit: The Imitation Game and Social Fluency.” Sociology 48(1):3–19.

[16] Philippe Ross (University of Ottawa), “How (Well) Do Media Professionals Know Their Audience(s)?: A Case Study of Radio-Canada Ottawa-Gatineau”

[17] Eric B Kennedy (Arizona State University) “Creating an Interview-Based IMGAME Method for Field Research”

[18] Shannon Conley (James Madison University), “Developing a Theoretical Scaffolding for Interactional Competence: A Conceptual and Empirical Investigation into Competence versus Expertise”

[19] John McLevey (University of Waterloo), “How do face-to-face and virtual networks shape the development of specialist expertise?”

[20] Duan Chengrong (Renmin University), “China’s 250 million Floating Population”

[21] Professor Duan has interviewed migrants who have been living and working as a floater for more than 30 years.

[22] National Bureau of Statistics, China Statistical Yearbook 2015 (Beijing: China Statistics Publishing House, 2015).

[23] National Bureau of Statistics, China Statistical Yearbook 2010 (Beijing: China Statistics Publishing House, 2010).

[24] Collins, Harry, and Robert Evans. Rethinking expertise. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

[25] Turing, Alan M. « Computing machinery and intelligence. » Mind 59.236 (1950): 433-460.

[26] Collins, Harry M., Robert Evans, Rodrigo Ribeiro, and Martin Hall. 2006. “Experiments with Interactional Expertise.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 37(4):656–7

[27] See also SAHIN, Ozan. « L’Intégration en tant qu’expertise interactionnelle : L’Imitation Game comme outil de mesure du niveau d’intégration des étrangers en Suisse ». Non-published M.A thesis, University of Geneva. (A printed version is available at the Geneva University library in UniMail. An electronic version can be requested from the author of this article).

[:en]Ozan Sahin

This article reports on the 11th annual meeting organised by researchers working in the field of Studies of Expertise and Experience (SEESHOP11). The workshop was hosted by the Confucius Institute of University of Geneva and was held on 20-21 May 2017 and continues a series that has included meetings in Cardiff University (UK), University of California (US), Arizona State University (US) and University of Waterloo (CAN). During the workshop, which was held in the Confucius Institute’s dazzling 19th century villa Rive-Belle, we hosted a total of 19 researchers from social science, humanities and law faculties around the world. This article is a brief report of this event and how it is related to Chinese studies and the works of Confucius Institute.

Context: Studies of Expertise and Experience

Decision making in public domain has never been an easy task, especially in the democratic societies where decisions that concern a much broader public may be taken by a few specialists. The difficulty is how to ensure that the choice of the few “specialists” is indeed the best option for the general interest. This is not just a matter of abstract values such as democracy or the general interest, because these decisions often have concrete and practice consequences. For instance, catastrophes caused by human error such as Chernobyl and challenger, or more recently the Fukushima incidents made us think, once again, on the question of specialist expertise, and the legitimacy of such experts’ in the processes that frame and inform decision-making in the public domain. Notably, the emerging field of Studies of Expertise and Experience (SEE) has become a realm in which researchers from various disciplines can investigate the nature of knowledge and expertise, as well as how they are being produced, acquired and transmitted within a society.

The debate about the nature of knowledge has a long history but one particularly important moment for SEE is Michael Polanyi’s introduction of the idea of “tacit knowledge”[1]. The idea of tacit knowledge can be best illustrated with an example. Imagine you are walking in your neighbourhood and someone asks you the direction to go to the closest bank. Having the correct information about bank’s localisation you are perfectly able to describe how to go to the bank: continue straight, after the traffic lights turn left, and then turn right, etc. Now, imagine that the same person wants to go to the bank by bicycle but that she doesn’t know how to ride a bike. Assuming you are the best cyclist in your city, the person now asks you to tell her how to go to the bank by riding a bike. You can still use a very clear language and give the instructions of which direction to go, but when it comes to explain how to ride a bike the language does not seem to reflect your true degree of knowledge on bicycling. Polanyi calls this type of knowledge “tacit knowledge”, a type of knowledge that cannot be manifested in explicit terms, at least by the sole use of the language.

In their previous works, Professors Harry Collins and Robert Evans from Cardiff University, have argued that science studies can be described as going through three waves[2]: a first wave where the only plausible and legitimate knowledge is that which is a product of objective scientific research, a second wave in which science studies scholars adopt a more constructivist perspective and recognise the necessity of social and cultural factors in the production on scientific knowledge; and a third wave of science studies in which the focus shifts from the deconstruction of truth to the reconstruction of expertise[3]. In particular, Collins and Evans argue that STS should explicitly address normative questions such as the role of scientists and others in the making of technological decisions in the public domain. It was this paper, and the research agenda it set out, that gave birth to the SEE[4] and a series of international workshops (SEESHOPs) devoted to developing its theories and methods[5].

Theories of Expertise in Action

One of the domains in which SEE researchers are exploring issues relating to expertise is the field of law. SEESHOP11’s law session, which was led by Professor Nicky Priaulx, from Cardiff University, included Ann Potter’s work on “Judging social work expertise in care proceedings” in Great Britain[6]. Potter, from Manchester Metropolitan University, presented the insights of her research and showed that since the adoption of the new Children and Families Act in 2014 there have been changes in the ways independent experts are used when taking decisions about whether a child should be removed from their family. Apparently, judges now rely on the much more extensively on information provided by the social workers as evidence. Potter’s research can help us explore and understand the consequences of this decrease in the number of independent experts in the care proceedings.

In the same session, Jaako Taipale, from the University of Helsinki, presented his work on dilemmas judges face when choosing the ‘right’ expertise in a trial where the parties might bring up to six different experts on medical science and technology[7]. The latter being a relatively new and controversial matter, there are numbers of issues where experts’ opinions present many disagreements. In his research, Taipale is interested in analysing “judges’ discrimination of factual evidence” when choosing which expert(s)’ opinion to accredit. Finally, Professor David Caudill from Villanova University presented his work on the practice of hiring “dirty experts” before a process of litigations in US courts[8]. The purpose of this practice, apparently very common in the US, is to make a kind of simulation so that they can note down what kind of arguments can be developed against the real or “clean” experts that will be used in the trial itself. Whilst this practice may serve the laudable purpose of reducing the likelihood of bad science being presented in court, it may also have the (unintended) effect of preventing the court from considering the impact or other, more legitimate, controversies.

In our days where the technological progress means that machines are slowly replacing humans to execute certain tasks then machines may be considered as ‘experts’ in those tasks, bringing us the questions about how ethics and accountability of these practices. In this context, Jathan Sadowski[9], from Arizona State University, examined how algorithms written for computer programs are used to assist and inform decisions about the sentencing of offenders and in predictive decisions made by police forces about where and how to allocate resources. Collin Robertson[10], on the other hand, showed how the development of new technologies for connected devices such as mobile phones and tablets can open the doors of science wider than ever to the broad public. He argued that environmental issues have the potential to increase the opportunities for citizen-scientists to collect and analyse scientific data. In this respect, Robertson’s work highlights one of the ways in which theories and methodologies developed by SEE can be used to promote developed and accountable modes of participation for ordinary citizens in different stages of scientific research.

Michael Gorman[11] also focussed on expertise, but in the context of commercial organisations rather the public domain. He was particularly concerned with contexts in which relevant actors – either internal and external to the organisation – are unable to avoid deviant practices such as in the cases of Challenger and Columbia disasters[12], or Gorman’s example of the collapse of Enron oil company. With this example, Gorman demonstrated how deviance can be normalized within the organisation and he argued that “interactional experts”[13] can bring solutions as their expertise enables them to understand problems from different, and sometimes competing, perspectives. In a similar way, Darrin Durant[14] is questioned the trade-off between the democracy and the ceding of authority to so called “experts” via two case studies, the South Australian blackout of September 2016, and the current Canadian nuclear waste disposal repository process.

Imitation Game Research

In addition to new theories of expertise, SEE has also developed a new method – the Imitation Game – designed to explore the nature of one particular type of expertise — interactional expertise – and a number of papers at SEESHOP 11 reported on applications of the method.[15] Philippe Ross[16], associate Professor from University of Ottawa reported on a study in which he had used the method in media studies research to explore how well media professionals who are implicated in the production of media commodities know their audience. Eric Kennedy[17], used the example of US fire department, where executives from different specialisms must collaborate in order to deal with an emergency situation, to propose a combination of survey methods and interview based Imitation Games that could collect scientific data but also provide solutions to the problems of communication between different domains of expertise.

In her presentation, Shannon Conley[18] made a distinction between expertise and competence, arguing that we should not necessarily search for experts in a specific domain, but maybe consider the importance of competence by putting the emphasis on “interactional competence”, which is the ability of executing a task acquired through socio-professional relations rather than an institutional certification. In a similar vein, John McLevey[19] argued that researchers often confound the three distinct categories of information, knowledge and expertise and that social networks researchers in particular often ‘ignore the empirical questions about knowledge’; the typology of expertise provided by SEE provides one way of avoiding this problem.

Researching Chinese Migrations

As we see, SEE has insights that may interest many disciplines and domain of research, and Chinese studies is no exception. For instance, Confucius Institute is administering a research project on migrations, integration and diversity in modern China that links Chinese studies and SEE. Before explaining the project in more detail it is necessary to explain some important facts about contemporary China and, in particular, the unique demographic phenomenon of its “250 million floating population”[20].

For the occasion of the 11th meeting of the SEESHOP, the Confucius Institute invited Professor Duan Chengrong, a specialist on Chinese migrations, to give a public lecture on the subject. Professor Duan’s works are very helpful for understanding this colossal human flux in a society where the movement of populations is highly regulated.

The characteristics of China’s internal migrations are determined by its unique family registration system called hukou (户口) under which most migrants keep their official residence in their hometown. The creates two distinct kinds of migration:

- Migration with hukou, which accounts for about 25-27 million people annually, and which grants migrants an official status that gives them rights to state services such as employment, schooling, health care and so on as other local residents,

- Migration without hukou (the 250 million floating population) where migrants have such official status and, as a consequence, no formal right to access to these public services.

Before 1978, it used to be almost impossible for Chinese citizens to migrate without hukou. Since the early 1980s, however, this has started to change, with the rise of China’s economic development and the emergence of private sector has creating a growing need for labor in the cities. As a result, many people living in the rural areas, where they may have difficulties gaining employment in agricultural production, have chosen to move to the cities where new opportunities being created every day. Although living and working in the city, these people do not have urban hukou and for this reason are called “the floating population” 流动人口[21].

In his lecture, Professor Duan described his research and the trends in the evolution of China’s migrations that it had revealed. First of all, we note a very sharp increase in size of the floating population. In the 1980s there are only about 6 million people in the whole country living as migrant; by 2015 this number had become 250 million, an increase of about 40 times in a few decades. This increase is not without consequences. Dealing with the problems and needs of this huge population is very difficult for the government, especially when we consider that a significant proportion of these migrants are unofficial, which means their presence — but also their problems and needs – may be invisible for the authorities.

Second, we also observe a strong concentration of migrants in the coastal cities as these constitute the most developed regions of the country. These cities offer new job opportunities and better living conditions for the new arrivals that the rural areas they are leaving. The combined effect of the rapid increase in the number of the floating population and the choice of developed coastal regions results in a high concentration of the floating population in cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, which have floating populations of 8.22 million and 9.81 million migrants respectively[22]. With these numbers, we note that in Beijing the floating population makes up 35.9% of the total population and in Shanghai the proportion is 39%. In Shenzhen, the floating population is an even higher proportion – 77% — with a total floating population of 7.7 million migrants![23]

Finally, the age pattern of the floating population and the motivations for migrating are also changing. Before, most migrants were working age people, but today there is a tendency for migrants to bring their families with them, sometimes even their parents, who not only accompany them throughout the migration process but become, themselves, migrants. Likewise, there are more and more women moving, either independently or with their families. The new comers are often better educated and work in skilled jobs.

Professor Duan concludes that these changes are reshaping the migrants’ profile in today’s China, and the country remains unprepared for the needs of such a large floating population that has distinct characteristics. In particular, without expertise on the evolution, experiences and aspirations of the floating population, they risk developing policies that are ineffective and fail to manage this unique demographic phenomenon. In the remainder of this article, an ongoing research project within the Confucius Institute of Geneva University, and a relatively new and innovative method for studying the socio-cultural integration of China’s floating population, that aims to address this problem directly will be will be described.

Researching Migrants in Beijing

The position taken in this study is to consider that the members of any given social group are experts in their own culture. For example, a person who was born and lived all her life in Beijing would know what it is like to be a Beijinger (i.e. an expert in Beijing culture). In the same way, we can accept migrants as the experts of their own, rural, culture but the crucial question for their integration is whether they can also become experts in the culture of their new, urban, home. Using theories developed by SEE, we can argue that a non-member of a society – i.e. a newly arrived migrant – can, after spending enough time within that society and having prolonged social relations with its genuine members, can develop enough knowledge about the culture and practices of that group to enable her to hold meaningful discourse with them. In the language of SEE, we would say that the migrant has developed interactional expertise in the practice of being a Beijinger. The concept of interactional expertise developed by Collins and Evans[24], is important because it suggest that different groups can come to understand each others’ experiences even if they do not share fully in each others’ practices. In other words, migrants and Beijingers can come to understand each others’ experiences through shared talk even if they lead lives that otherwise very different. The question to ask at this point is “how do we know if somebody has interactional expertise?” The answer lies within the Imitation Game.

Initially known as the “Turing test”[25], the Imitation Game is a quasi-experimental method that generates both qualitative and quantitative data. In its most simple format, it is a game played by individuals who are drawn from two different social groups whose experiences are assumed to be different in some way (i.e. men vs women, migrants vs locals, etc.). Participants to the Imitation Game are required to play three roles; the role of judge in which they formulate questions and ask them to the other participants, the role of pretender, played by a member of the other group who is tasked with trying to convince the judge that they are the members of the judge’s own social group (i.e. if the judge is a Beijinger, the pretender would be a migrant who should try to convince the judge that she is also a Beijinger), and Non-Pretender (a genuine Beijinger in this example) who must answer honestly. The aim of the game is for the Judge to set questions and, by comparing the answers, work out who is a member of which social group. If the judge is not able to identify the pretender correctly, then we say that the pretender has interactional expertise in culture of that social group as she is able to take part in the discourse of that culture without being disclosed as an outsider.

The method, after being introduced by Collins and Evans in 2006[26], has been funded by the European Research Funds in 2011 for a five-year research project, and since then it has been used in a large variety of studies. One of the fields that the method has been applied is the migration studies. Notably, Confucius Institute’s PhD candidate Ozan Sahin is combining the Imitation Game method and the SEE theories with that of Chinese studies for his research on the socio-cultural integration of Hebei migrants’ in Beijing municipality[27]. The objective of this study is to explore how different social groups, in this case “migrants” versus “locals”, interact with each other within urban areas. The findings are expected to help understand:

- How the members of different social groups identify themselves with regards to other social groups

- Their vision and understanding of other groups’ members

- How cultural differences influence migrants’ integration?

In Beijing, migrants from the same city or province often prefer to live and work in the same compounds as their fellow villagers, where they often work excessive hours for a very low income. Many don’t see anywhere other than their working and living space and have little or no interaction with local people. We argue that this is likely to leave migrants’ isolated from the host society and make it difficult for them to fully integrate into the urban life. Thus, the purpose of this research is to apply the Imitation Game method to measure the correlation between the intensity of interactions with the local population and the level of migrants’ integration.

Before adapting the method for his research, Ozan Sahin and Xu Jia from Renmin University organised two trial sessions of Imitation Game at the Renmin University of China in the summer of 2016. Below we present the first findings of this research.

For the first trial session of the Imitation Game, a total of 10 Chinese participants were took part (5 Beijingers and 5 migrants) and 48 target expertise questions were asked. We recorded the dialogs between the players and created question-answer sets for each player (see figure 1 below). When analyzing the results, we noticed that questions asked by Beijing judges can be grouped into 5 general categories: food and beverage, places in Beijing, language use, origins and Olympic games. These categories and their sub-categories are shown in the table 1 beneath.

From these findings, we notice that most of the Beijing judges (i.e. participants of the experiment who are originally from Beijing) ask questions which are related to migrants’ experiences and knowledge about peculiar places and local culture of food and beverage which, we assume, they think migrants will not have experienced. If we do accept the Beijing judges as experts of their own culture, we can observe that for them the criteria that distinguishes a Beijinger from a migrant consist of – or at least includes – having enough information about these subjects and being able to talk about them as if it is a part of one’s own culture. Interestingly, the expectations of the Judges were sometimes confounded as our research found that the success rate for migrants pretending to be Beijingers is about 60% (3 out of 5 players convinced the judges that they are locals), suggesting this knowledge is more widely distributed than Judge’s thought and that migrants are better integrated (at least in the sense of having interactional expertise) than Judge’s expected.

That said, it must be noted that our sample was very small and was mainly composed of university students. As such, these results cannot be used to make any general conclusions. Nevertheless, they have been useful in drawing out some general features of the floating population and, most importantly, developing a new version of the Imitation Game software for Chinese users that will enable us to widen our population sample by having more participants with more diverse profiles. For this purpose, the author of this article is developing, with the collaboration of Jacky Bossey from SAE institute Geneva, a new version of the Imitation Game software specifically designed for Chinese users: 伊迷他心 (Yī mí tā xīn, literally “(S)he cheats his heart”).

One of the objectives of this research is to go beyond simply identifying the problems experienced by migrants and to offer possible solutions. For example, by playing Imitation Games over a period of time, it will be possible to observe the effects of an increase in the interactions between the migrants and the local population. Such an increase can be encouraged and facilitated within the Imitation Game by, for example, distributing vouchers to participants that enable them to visit a cultural monument, restaurant or other cultural space with one or more players from the other group. In this way, the Imitation Game can be used to offer migrants access to the local culture and, in so doing, increase their stock of interactional expertise. As players who have received such vouchers return to play new sessions of the Imitation Game we will be able to compare the results obtained before and after the intervention and see whether an improvement in terms of migrants’ integration (i.e. an increase in their level of interactional expertise) has occurred.

Cette contribution a été relue par Robert Evans

SAHIN, Ozan. « From technocracy to citizen science: The nature of expertise and the place of experts in our societies ». In Blog Scientifique de l’Institut Confucius, Université de Genève. Lien permanent: https://ic.unige.ch/?p=1131, consulté le 04/19/2024.

[1] Polanyi, M. (1967). « The tacit dimension ».

[2] Collins, H. M., & Evans, R. (2002). « The third wave of science studies studies of expertise and experience ». Social studies of science, 32(2), 235-296.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See also SAHIN, Ozan. (2014). « L’Intégration en tant qu’expertise interactionnelle : L’Imitation Game comme outil de mesure du niveau d’intégration des étrangers en Suisse ». Non-published M.A thesis, University of Geneva. (A printed version is available at the Geneva University library in UniMail. An electronic version can be requested from the author of this article).

[5] SEE can be thought of has having two elements. A ‘technical’ element that focuses on the nature of expertise and which is best summarised in Collins and Evans’s (2007) book Rethinking Expertise, and a political element that focuses on the relationship between expertise and democracy that is set out in their more recent Why Democracies Need Science (2017).

[6] Ann Potter (Manchester Metropolitan University), “Judging social work expertise in care proceedings”

[7] Jaako Taipale (University of Helsinki), “The usefulness of meta-expertise in examining judges’ discrimination of evidence”

[8] David S. Caudill (Villanova University), “Dirty experts: their use, and what they tell us about law’s appropriations of expertise”

[9] Jathan Sadowski (Arizona State University), “Predictions and Premonitions: Algorithms as Experts in Sentencing and Policing”

[10] Colin Robertson (Wilfrid Laurier University), “Environmental citizen science as a novel application for studies of expertise and experience”

[11] Michael E Gorman (University of Virginia), “Trading zones, interactional expertise and moral imagination”

[12] See also Vaughan, Diane. « The dark side of organizations: Mistake, misconduct, and disaster. » Annual review of sociology 25.1 (1999): 271-305.

[13] People who have acquired a certain level of expertise only by the means of intense interactions with the certified experts. (Also see “interactional expertise” below.)

[14] Darrin Durant (Melbourne University), “Saving expertise”

[15] For details of the Imitation Game see: Collins, Harry M. and Robert Evans. 2014. “Quantifying the Tacit: The Imitation Game and Social Fluency.” Sociology 48(1):3–19.

[16] Philippe Ross (University of Ottawa), “How (Well) Do Media Professionals Know Their Audience(s)?: A Case Study of Radio-Canada Ottawa-Gatineau”

[17] Eric B Kennedy (Arizona State University) “Creating an Interview-Based IMGAME Method for Field Research”

[18] Shannon Conley (James Madison University), “Developing a Theoretical Scaffolding for Interactional Competence: A Conceptual and Empirical Investigation into Competence versus Expertise”

[19] John McLevey (University of Waterloo), “How do face-to-face and virtual networks shape the development of specialist expertise?”

[20] Duan Chengrong (Renmin University), “China’s 250 million Floating Population”

[21] Professor Duan has interviewed migrants who have been living and working as a floater for more than 30 years.

[22] National Bureau of Statistics, China Statistical Yearbook 2015 (Beijing: China Statistics Publishing House, 2015).

[23] National Bureau of Statistics, China Statistical Yearbook 2010 (Beijing: China Statistics Publishing House, 2010).

[24] Collins, Harry, and Robert Evans. Rethinking expertise. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

[25] Turing, Alan M. « Computing machinery and intelligence. » Mind 59.236 (1950): 433-460.

[26] Collins, Harry M., Robert Evans, Rodrigo Ribeiro, and Martin Hall. 2006. “Experiments with Interactional Expertise.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 37(4):656–7

[27] See also SAHIN, Ozan. « L’Intégration en tant qu’expertise interactionnelle : L’Imitation Game comme outil de mesure du niveau d’intégration des étrangers en Suisse ». Non-published M.A thesis, University of Geneva. (A printed version is available at the Geneva University library in UniMail. An electronic version can be requested from the author of this article).

[:]